We had been wanting to do this for a long time, and finally, we found the right moment. At GALEO, we had long wanted to launch a community where we could share our ideas, questions, and challenges, all grouped under the concept ChipToCloud.

The idea behind the slogan is simple, and it is closely linked to what we do every day.

Digitalization has had a very significant impact on many aspects of our lives, and consequently, on many aspects, processes, and administrative and business systems. Moreover, it has happened at a breathtaking speed. Just look at how banking, insurance, tourism, and many other sectors and services have been transformed.

However, the impact of digitalization on the physical economy — in sectors that involve real, not virtual, assets, such as industry, manufacturing of capital goods, automotive, infrastructure management, or construction — is proceeding much more slowly.

I don’t have a clear explanation for this difference, but here is an attempt: it is much more complex. Where does this additional complexity come from? I don’t have a complete explanation either, but here are some contributing factors:

- The physical world is necessarily distributed. Assets, equipment, and infrastructures are spread across territories, in diverse local conditions, with variable connectivity capabilities that depend on factors difficult to manage.

- Digitalizing the physical world requires the collaboration of systems across multiple layers, with different technologies and protocols. This clearly represents the concept ChipToCloud. It reflects the idea of designing systems capable of integrating and coordinating digital components embedded in a chip, in a control system, and in multi-protocol connectivity systems (from electronic signals and industrial protocols to the TCP/IP stack used by digital systems). Moreover, each layer has different processing architectures — chips, PLCs, servers, and cloud services — which must also be integrated and coordinated.

- Digitalizing physical assets has more demanding requirements for quality and functional response. A mistake in a banking transaction — however painful — is easier to fix than a car crashing into a building. Digitalized physical systems must guarantee their behavior in critical conditions, which imposes stricter demands — including stricter regulation — on their design and development.

- Digitalizing infrastructures and physical assets must ensure long-term operation. Once sold, a car must guarantee its functions and features for at least 10–15 years. Industrial machinery is acquired to operate robustly, continuously, and predictably for decades. By contrast, a digital system launches new versions and fixes errors every month. Reconciling these two visions of how things should work is a challenge far deeper than it may seem.

And perhaps most importantly: all these physical and digital assets we need to coordinate exist to serve people. They are operated, maintained, and managed by humans who make decisions based on data, but also on the experience and intuition developed over years of practice. This human participation is essential; it adds enormous complexity, but without it, there would be no purpose at all. Learning to integrate this critical human factor into our technological vision is essential for understanding both the world we live in and the one we are building.

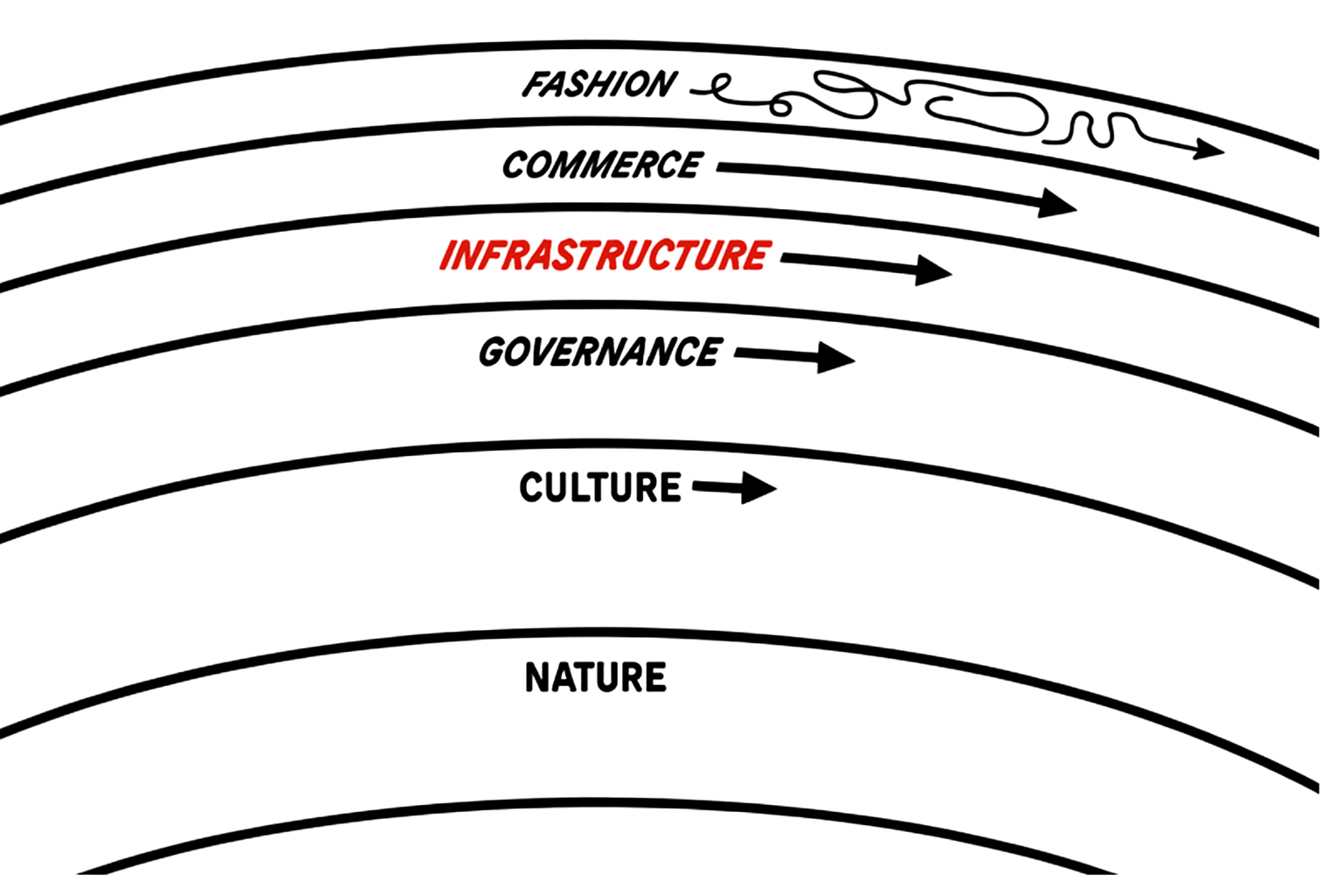

Stewart Brand of the Long Now Foundation proposes a layered model for analysing how civilisations transform. Each layer has a different rate of change, from the rapidity of changes in tastes and fashions to the rigidity of changes in the natural environment. Each layer influences its adjacent layers, promoting changes in the slower adjacent layer or imposing friction on the nearby layers that transform more rapidly [1].

It seems to me that the model proposed by Brand accurately describes the complexities we face in addressing the challenge —and opportunity— of digitising our physical environment, its infrastructure, and processes.

Purpose

I am not sure if these are exactly purposes, because perhaps they lack concreteness. But behind the concept ChipToCloud that I have just presented, aspirations emerge that shape the way we approach the projects we get involved in.

Simply reflecting and the curiosity awakened by the vision of ChipToCloud digitalization is a powerful intellectual motivation for any restless mind interested in understanding the context we live in. But since we are engineers, we do not like to stop at thinking; we like to learn and discover by doing. As we often tell ourselves here: “those who do not do, do not know”.

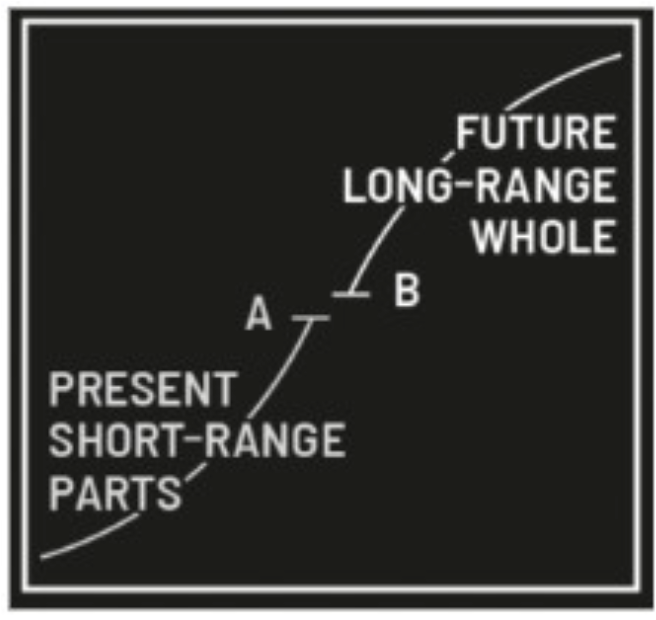

So the first aspiration is purely engineering-driven. It consists of the ambition to design mechanisms and technologies that allow us to understand and control these increasingly complex systems. As engineers, we seek ways to build capabilities that allow us to predict and control these systems through the coordination of their digital and mechanical components, as well as their structures and procedures.

This first aspiration is essential to feed the next one, which is our commercial aspiration, as digital engineering professionals, as a company. Our purpose is to work with our clients so they can offer better products and services. And we are convinced that to achieve this, it is essential to adopt solutions that digitalize their businesses from chip to cloud, and that help them improve quality, optimize costs, and differentiate themselves in the market.

But note: an engineer is not an inventor. We like to see things working, producing results, and expanding their impact in real and daily life. As entrepreneurs, we are satisfied with keeping a portion of the benefits obtained by our clients.

Beyond these aspirations, there is a community-related one, which is as important as the others. The aspiration that we integrate these digital capabilities into the management of the common — which is not only public, but also shared — thereby ensuring that our communities have useful goods, services, and infrastructures that improve their quality of life in the long term. Also, that we are able to build these systems to use our resources, everyone’s resources, efficiently, robustly, and sustainably.

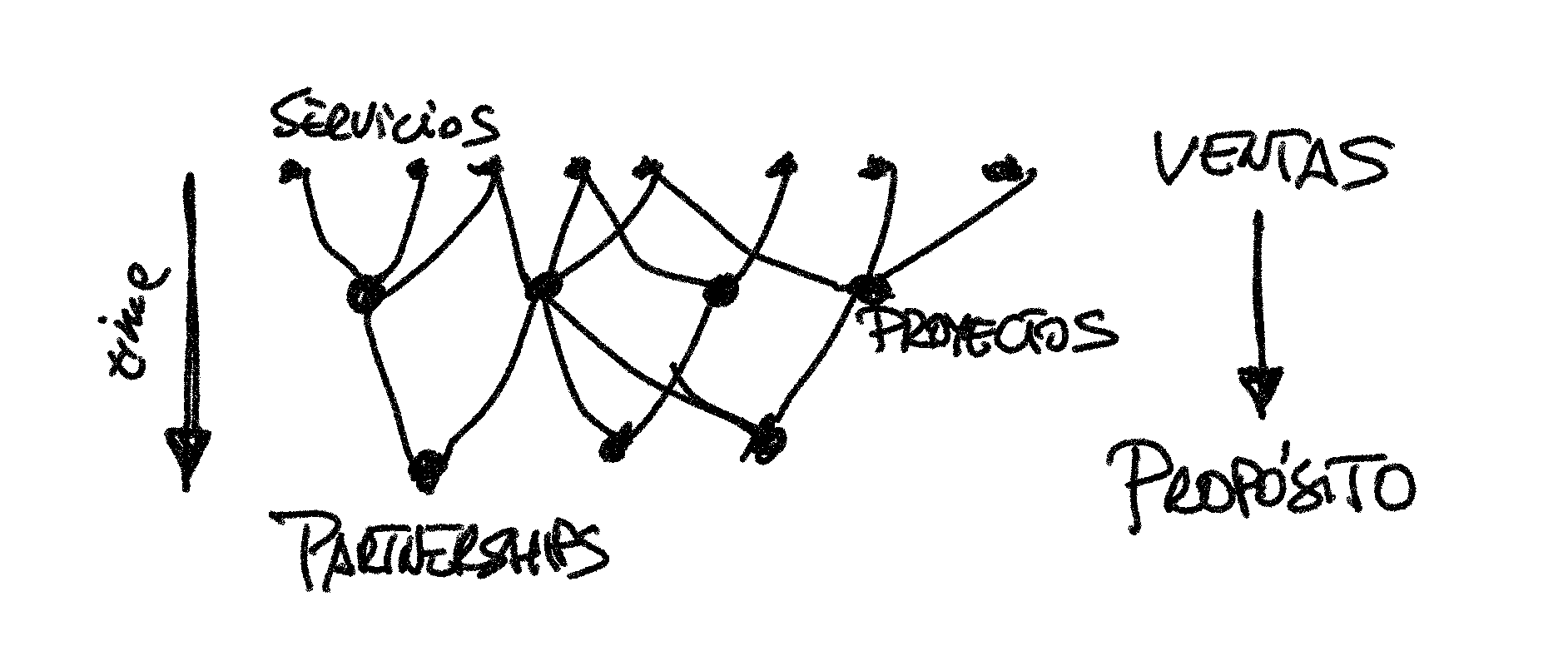

Satisfying these aspirations is something we cannot do alone. Neither we nor anyone else. The nature of the systems we want to transform and improve, the knowledge and experience required to do so, and the coordination of all the agents and organizations involved, requires the participation of many actors. So many that it may be better to say it requires the participation of everyone. Fostering this participation, creating spaces where all actors can meet, giving ourselves the time to understand and debate the different perspectives posed by the challenge of digitalizing infrastructures — that is the purpose of the ChipToCloud sessions [2] that we finally organized in Oviedo on September 30 and October 1.

Debate

You can find information about the sessions on the event page. I will use these lines, first of all, to thank everyone who attended; everyone who got involved, supported, and even financed the initiative [3]; but I want to particularly thank all the collaborators who generously agreed to share their experiences [4]. I also want to thank the sun for shining those days — in Asturias, these things are appreciated — and allowing us to showcase our new offices in the spectacular Purificación Tomás park in Oviedo.

One of the difficulties we continuously face in the context of digitalization initiatives in these sectors is that we do not understand each other. We all belong to different tribes that speak different languages. Many different languages. Some use the language of business, others that of technology experts; for some, digitalization is in the cloud, for others it is industrial machines, in operation and control; some speak of services, innovation, and customers, while others focus on costs, efficiency, and savings.

Using these languages, each tribe has built a representation of reality, a mental model of the systems we need to create and manage, and with this representation a vision of how they should evolve, what the relevant problems are to adapt them to changes in context. Each one, a movie.

But if we dedicate time, if we create conditions to listen to each other without the pressure of daily life, without the tensions that commercial relationships sometimes produce, the important debates naturally arise:

Are we addressing the relevant problems?

Are we ensuring that the systems we create will be able to adapt and evolve?

Or are we really focusing on solutions that will be replaced by others increasingly quickly?

When we digitalize infrastructures, factories, or territories, can we allow ourselves ephemeral solutions?

Are we building the digital infrastructure we will need in the future?

Or are we playing with pieces that are just trendy?

Are we capable of understanding the complexity of the challenge?

Do we have ecosystems prepared to tackle them?

Do we have collaborators, suppliers, and employees capable of doing so?

These questions, and their corresponding debates, arose throughout the sessions. We were able to hear the perspectives of entrepreneurs and engineers; of the administration, of executives with long experience, but also of students about to join the workforce — all concerned with preparing to be useful in this context that evolves continuously and ever more rapidly and complexly.

Takeaways

I take away several lessons from the debates that emerged at the event, in the talks, and during the coffee breaks. Some require processing and digestion, and others will surely reverberate more casually in the future. But I want to highlight three conclusions that have impacted me especially.

Ángel Llavero, from Meltio, emphasized the importance of people — both the engineers who develop technological solutions and the users who apply them in their daily activities. But what I found particularly relevant was his view of the process of selling and adopting technological solutions as a knowledge transfer process between the engineer who develops and the end user. It is a perspective we seldom consider, and one in which AI will play a particularly relevant role in the coming years.

Joaquín Abril Martorell, from Nanomate, impressed us all with his reflection on the need to rethink governance models that regulate strategic investments in technology, and how those governance models ultimately impact operational capabilities day to day. One example discussed was the impact of not having a European cloud provider, and the difficulties this creates for critical sectors such as administration, healthcare, or defense to adopt cloud technology. The limitation of access to innovation, efficiency, and agility due to the lack of a geopolitically reliable cloud provider is a risk that we have been ignoring for a long time. Similar challenges exist regarding the limited production capacity of semiconductors or the scarcity of basic materials for chip manufacturing in European economies.

Perhaps the lesson that resonates most clearly comes from a reflection by Álvaro Platero, from Astilleros Gondán. Faced with misunderstandings, the problems of our own languages and agendas, and the difficulties in being useful to each other, Álvaro suggested that we seek time and patience to get to know each other better. Everyone. Technology providers with industrial entrepreneurs; engineers and technologists with users and financial directors, experts and newcomers.

I take away the idea that, to be ambitious, to satisfy the aspirations mentioned at the beginning of this post, to carry out more impactful projects, and to establish more enduring and valuable relationships, we need to stop selling. In reality, to sell more and better, we must stop selling. Stop selling things to each other, and start talking to understand each other. And better than talking — start listening.

Facilitating this conversation was the motivation for launching the ChipToCloud initiative from GALEO. Now, it is up to all of us to continue it, and if you have read this far, my sincere thanks for your interest and my sincere invitation to join the conversation.

[1] Stewart Brand: Pace Layering: How Complex Systems Learn and Keep Learning, 2018. Long Now Foundation.

[2] www.chiptocloud.tech, 2025.

[3] Firstly, the GALEO team, Luisma Hernández Valencia from Asturias Power, the Sekuens Agency of the Principality of Asturias, the Oviedo City Council, and surely someone else whom I have now forgotten.

[4] Angel Llavero (Meltio), Richard Villaverde (CAPSA), Luis Pérez Castaño (Gonvarri), Isabel Caviedes (Alhona), Salvador Bohigas (MSI), Álvaro Platero Alonso (Gondán), Iñigo Olarreaga (Iberdrola | BP Pulse), Patricia López (Idonial), Sergio Baragaño (Room2030), Iván Aitor Lucas del Amo (Principality of Asturias), Joaquin Abril Martorell (Nanomate)… and all those in attendance who participated in the debate.